Dementia Care and COVID-19: How do we move forward?

By Bonnie Burman, The Ohio Council for Cognitive Health

and Jennifer Brush, Brush Development and Consultant for the Ohio Council for Cognitive Health

All of us have been impacted by COVID-19 in many ways, both professionally and personally. The presence of the virus has also created some significant challenges for those living with dementia, especially for those living in long term care communities. In addition, as states work to reopen or partially reopen care communities, the common misunderstanding that individuals living with dementia cannot practice social distancing may result in their continued unnecessary and harmful isolation.

Individuals with dementia have the same needs as everyone else—to feel valued and respected. As dementia progresses in the brain, memories of facts and skills for complex thought fade but feelings such as happiness, love, frustration, and sensing respect remain. “Treatment” for dementia is socialization or elimination of boredom.

There are two enemies out there right now: the virus and isolation.

While public health officials at the state and local levels are currently working carefully, diligently and effectively to both curb the spread of COVID-19 and ensure that emergency operation plans for pandemics are in place going forward, social distancing among those living with dementia has posed unique challenges.

The question we are asking is…

“Are misunderstandings about dementia and best practices resulting in less than optimal engagement and unnecessary social isolation during COVID-19?”

And our answer is a resounding…

“YES!”

Many individuals living with dementia can practice safe social distancing with the appropriate person-centered care practices and procedures in place. This is especially important now as states move to partially reopen care communities to visitors when social distancing can be practiced.

The Ohio Council for Cognitive Health and Brush Development are suggesting a focus on the following:

4 common misunderstandings about people living with dementia that may result in unnecessary and in fact harmful isolation:

- It’s impossible to keep people living with dementia 6 feet apart, so it’s safer to keep them in their rooms all day.

- People with dementia will never remember to wash their hands or to keep surfaces sanitized.

- Staff cannot effectively communicate with someone with dementia while wearing a mask.

- It hard to keep someone with cognitive impairment engaged in something for very long.

This article focuses on these challenges by 1) shedding light on the current issues; and 2) providing examples of responses that address the unique vulnerability of those living with dementia. Most specifically, there are cost effective and responsive ways to adhere to social distancing and other current health and safety protocols that do not result in social isolation and the unwanted/unintended behaviors that may result. We cannot ever be too busy to foster relationships and engage elders living with dementia in a normal, purpose driven day. Unnecessary social isolation as a result of COVID-19 for those living with dementia puts elders at risk for decline in mental and physical functioning, loneliness, and depression when, in fact, many can practice social distancing.

Why is this so important?

This is especially important because the vast majority of elders living in long-term care settings have some cognitive impairment even though it is not always diagnosed. Some of these elders living with significant cognitive changes live in separate memory care units. These units have been recognized for over 20 years but remain largely unregulated in many states. Standards and practices are still being defined and there is little consistency between them.

Approach

The recommendations, and the reframing provided, reinforce CDC published guidelines and provide care communities with evidence based, person-centered approaches and perspectives that will prove to be cost effective over time and will help them fulfill both their priority for safety and their important mission of ensuring maximum engagement for those impacted by dementia. Practical, person-centered approaches that add purpose to the daily routine of staff and residents while keeping everyone safe will be highlighted. These approaches will ensure that well-intentioned efforts of care communities don’t put those with dementia at risk for further cognitive or physical decline. These will include approaches that include engagement but also remain responsive to those who either need to stay in their rooms or apartments or those who want to stay in their rooms. Not everyone wants to be with other people.

What is person-centered care?

Person-Centered Care (PCC) is a philosophy of care that prioritizes the autonomy, enablement and self-determination of the person receiving care. Medical and professional staff as well as family members, partner with each individual to identify and capitalize upon his or her strengths, needs and capabilities. This collaboration results in a supportive delivery of services that are tailored to and directed by each. PCC was born out of a desire to de-institutionalize healthcare delivery and recognize that the person receiving care should be at the center of all that we do; that we should be treating the whole person; not just a disease or a set of symptoms. Furthermore, some residential communities enhance PCC by organizational restructuring with the goal of localizing decision-making so that staff are better able to respond to the preferences of the individuals living in the community.

Central to PCC are the core values of respect for the individual, the importance of knowing the elder deeply, seeking and honoring the person’s preferences over all aspects of their daily life, and creating a supportive environment that allows for continued participation in familiar and preferred activities, inside and outside.

Case example

We would like to introduce you to Michael. . .

Michael is an 86-year-old man living in a care community in Northeast, Ohio. He moved to the community because his wife could no longer provide the assistance he needs related to medication, bathing, dressing, and toileting as a result of vascular dementia, prostate cancer, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Michael worked as a technician for the telephone company for his entire career. His hobbies included woodworking, barbershop choral singing, gardening, bird watching, playing the piano, and fixing small machines and appliances. He served in the Army for a short time as a shipping clerk, raised four sons in Maine, and moved to Ohio 15 years ago to be near his oldest child’s family.

When the community was advised to close its doors to visitors and take precautions to reduce the risk of the spread of COVID-19, elders in the community were asked to stay in their room all day. The community put a two-page notice in all residents’ mailboxes about the virus, meals were brought directly to the rooms, and daily newsletters were distributed that contained trivia and word games. A treat cart with desserts and ice cream made its way through the halls each afternoon to spread cheer.

When staff came in Michael’s room to assist him with bathing and dressing, he repeatedly refused their help. Then the phone calls started. Michael’s wife received 8-10 phones calls a day from her husband, often starting at 6:30 AM. Repeatedly, he read what he could of the notice and newsletters to her, asking why she sent them and what they meant. The print was so small he could not make out all of the words. He asked when she was coming to visit and why his food was wrapped in plastic that he could not open. He called to let her know that he spilled his tray on his bed and that he wasn’t sure where his clothes were. His wife decided to visit by standing below his second story window. She called him on the phone and told him she was outside and to come to the window. He was unable to follow her directions to raise the window blinds and open the window. All she saw were hands moving around the edges of the blinds.

The family had a phone conference and decided to “mobilize the troops.” The sons set up a calendar schedule for calling their dad, one of the grandchildren created a personalized CD with all of Grandpa’s favorite music on it. Directions for using a simple CD player were created in large print. A card table, folding chair, nuts and bolts, tools, and sorting and sanding activities were assembled into kits. A memory book describing Michael’s life was create by his daughter in law. All were delivered to the AL along with a care package of favorite snacks. When his wife called to ask how he liked all of his gifts, Michael asked her to come and take it all away. By himself, he was unable to make sense of it all.

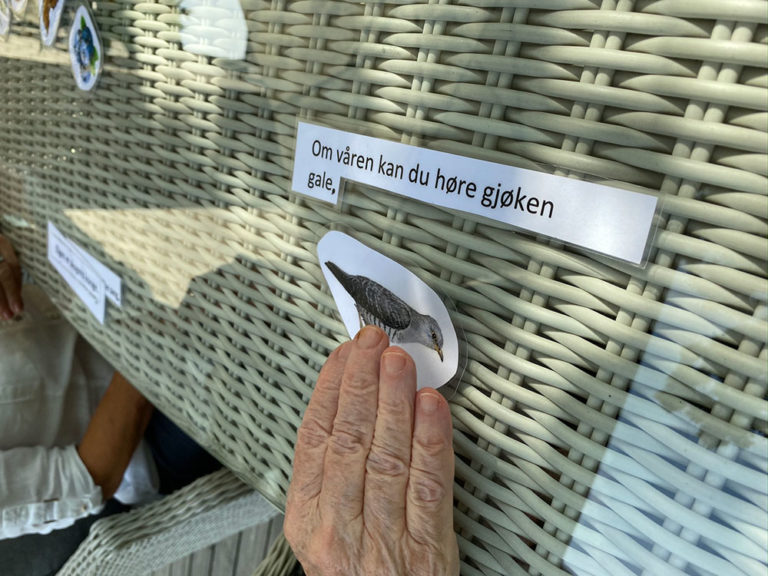

He needed someone to set up each item and slowly demonstrate how to use each item, relating each activity to his past and his interests. He needed opportunities to fix things, move, exercise and sing, just like he had his entire life. If someone had known his past preferences well and had been trained in dementia care best practices, staff could have opened the blinds and window, and set the table next to it. Michael could have looked outside, watched the birds and sanded a birdhouse while listening to his favorite music. The family were disappointed that this hadn’t been taken care of automatically and that they had to specifically asked the care community to staff to do this.

Finally, after 8 weeks, a life enrichment staff member, set up a virtual visit on her personal cell phone so that Michael and his wife could see each other. A sense of calm and relief set in as soon as their eyes met.

This care community had the very best intentions to keep everyone safe and to provide assistance and engagement. The problem is that person-centered care isn’t a one size fits all approach.

Key Questions

What have we learned from this story that will help us now and into the future and as strive to provide person-centered care?

Are misunderstandings about dementia and best practices resulting in less than optimal engagement during COVID-19? And, how are these misunderstandings impacting states’ efforts at reopening or partially re-opening long-term care settings?

Again, these are some common misunderstandings about people living with dementia that resulted in Michael’s isolation:

- It’s impossible to keep people living with dementia 6 feet apart, so it’s safer to keep them in their rooms all day.

- People with dementia will never remember to wash their hands or to keep surfaces sanitized.

- Staff cannot effectively communicate with someone with dementia while wearing a mask.

- It hard to keep someone with cognitive impairment engaged in something for very long.

These misunderstandings are widespread, and need to be dispelled.

Here is another way at looking at the situation that would have enhanced Michael’s sense of well-being while keeping him safe during COVID-19.

- People can sociably distance by engaging with different personalized activities at tables that are safe distance part, in their rooms with door open, and in small group activities in well ventilated areas. A small worktable with projects of interest would have relieved boredom and decreased anxiety. A schedule during which different people walked throughout the hall at different times of the day would establish a routine of movement while reducing the number of people in the halls at one time. Michael would have enjoyed purposeful cleaning, planting and weeding of outside spaces.

- People with dementia can learn new routines and can follow written cues, gestures and demonstrations by others. In Michael’s situation, a care partner could have invited him to participate in one of the sorting activities. She could have demonstrated the process with her hands positioned so that he could see them clearly and moved at a steady, unhurried pace. This would have allowed him to understand how to complete the activity and be independent engaging with the materials himself.

- Staff who deeply know a person can communicate with their eyes, body language, gestures, and habits that meet an individual’s preferences and needs. Staff could have doffed their mask briefly before entering Michael’s room or approaching him in order to greet him before assisting with daily care.

- Since music activates parts of the brain that are relatively spared by diseases causing dementia, it brings joy and enables those with cognitive impairment to engage in life. It has been documented to facilitate movement, speech, and memory recall. When care partners use these preserved abilities to compensate for the deficits associated with dementia, attention to task increases, responsive behaviors decrease, and affect improves. In Michael’s case, once he was cued to follow the written directions to use his music player, he found great comfort in the familiar tunes.

Focusing on the 4 basic needs that individuals living with dementia have, here are some best practices to consider during this time of COVID-19 and as we move forward.

Need #1

Allowing safe freedom of movement within the care community.

Everyone should have the opportunity to move about as freely as possible, but changes in the brain caused by dementia may mean that individuals are not able to exercise the judgment and reasoning to do it safely by maintaining a physical distance and wearing a mask. There are a number of reasons why a person with dementia needs to walk about such as the need to engage in a familiar routine, desire to find the bathroom, want of exercise, desire to relive boredom, etc.

Key Messages

Do not try to keep the person seated all day in order to stop the walking about. This may cause anxiety, boredom, incontinence, poor circulation, constipation and overall weakness, thus increasing the risk for falls. Walking helps elders to maintain balance, gross motor skills, and overall healthy functioning of the body’s systems.

Know the person

Leadership should empower all staff to take the time needed to get to know the person and to work with the elder on a routine that keeps the person engaged in activities that meet her or her needs.

Rely on what you know about the person and their past and present habits to try to figure out why the person would like to walk about. Consistent staff assignment is important in order to know the person’s preferences and habits. Once you have identified the cause or suspected cause of the behavior, you can try some solutions. You may have to try several different things before you find the right fit for the person.

Pay attention to when the desire for walking about occurs. It is common for an increase in noise to cause the person to want to get up and leave the area. Activity or noise that used to be easily tolerated or enjoyed such as the TV, radio, staff coming and going at shift change may be overstimulating and uncomfortable.

Ask the physician to help determine if the person is in pain, has a urinary tract infection, or is experiencing side effects of medications.

Create routines that involve movement

Suggest a daily walk. Accompanying the person at a safe distance on a daily walk or enlisting the help of family, friends or volunteers to walk in a safe location such as a courtyard is a simple solution that usually works very well. Build this into the daily routine.

Look for indoor opportunities in well ventilated areas for regular exercise such as an exercise class with a limited number of participants or seated exercises done with a video or internet-based tutorial.

Many people walk about out of boredom or because they are looking for something meaningful to do.

If the person enjoys a certain type of hobby, try setting up a hobby table in their room where they can go and work on a project whenever they like.

Provide cleaning materials such as a broom, dustpan and dusting cloths and invite the person to clean his or her room on a daily basis to encourage movement and purposeful activity.

Try to encourage a healthy sleep routine for the person and avoid napping during the day, particularly due to lack of things to do.

Provide orientation information

Provide information about the time of day. People with dementia often wake throughout the night and becomes confused about time. They may wake up in the middle of the night and get dressed. Having a large digital clock that shows AM and PM may help with the time confusion. Leaving a light on in the bathroom and the hallway may help reduce disorientation at night. Avoiding daytime napping and spending time outdoors will also help encourage normal sleep patterns.

Need #2

Protecting elders against COVID-19.

People living with dementia may find it difficult to understand health information and to remember to follow infection control guidance like washing their hands or wearing masks.

Key Messages

Information

Consider how much information to convey about COVID-19, to avoid inducing anxiety, but enough to convey the importance of following the guidance. Provide simple information that is easy to understand for a person with cognitive impairment in a large print type size that is easy for elders with visual impairment to read. Encourage the elder to talk about any fears or concerns. Listen, reassure, comfort, and try to maintain a positive attitude.

Handwashing

Help elders make frequent handwashing part of the regular routine. Create positive visual reminders such as signs for the bathroom that state, “Clean hands feel good.” Provide warm cloths at each meal for elders to use prior to eating. Provide encouragement and celebrate accomplishments when the elder remembers to wash his or her hands.

Make tissues, garbage cans, and sanitizer visually accessible throughout the community for easy access and a visual reminder to use.

Masks

Help elders make mask wearing part of the regular routine. After the morning routine, suggest placing a mask on one’s face before leaving the room. Provide a hook and reminder note inside the bedrooms, near the door, as a reminder to put on the mask before exiting. Provide staff with a positive statement (mantra) about using masks that each person uses in order to communicate the same positive message.

Remove masks prior to entering elder’s rooms in order to greet the person at a physical distance and allow the person to see the face of the staff member. Wear high contrast large print name tags with the person’s first name only and a large, clear photo of the person. Place name tags on the chest rather than hanging from a lanyard.

Look the person in the eye when communicating with a mask on, use positive gestures, and maintain a calm presence.

Need #3

Keeping families safely connected with their loved ones.

Social and emotional well-being of both family members and elders often is centered around maintaining frequent contact with one another. Because the physical distance required during COVID-19, families are concerned about their loved one’s health status. In addition, both parties can experience anxiety and loneliness from the separation.

Key Messages

Maintaining positive relationships

Assist elders and families with regular visual assess to their loved ones by setting up recurring appointments for video conferencing.

Provide assistance to elders to connect with loved ones routinely by phone.

Assist elders in writing letters, cards, or emails to family and friends. Provide cards, stationary, and stamps and invite the elder to dictate a letter (or email).

Provide family members with directions and a template for creating a memory book for their loved one. Ask family to drop off the book, or volunteer to print and assemble the book if the family emails an electronic file.

Suggest that families create a memory box or care package with a variety of interesting items such as photos, travel memorabilia, trinkets, favorite snacks, magazines, etc. for the elder to enjoy.

Limit family visits to two people at a time. Ask family members to wear masks and use sanitizer or wash hands immediately upon entering the building. Offer name tags to family members to assist the elder in recognition. Provide a variety of visiting space options in areas that can be ventilated by opening windows. Provide chairs for visiting throughout outdoor spaces.

Provide activity ideas for the families to enjoy together such as gardening, listening to music, games, taking walks, filling bird feeders, etc.

Need #4

Purposeful activity.

The need to have purpose in one’s life and to be productive doesn’t end once someone reaches a certain age, moves into a care community, or receives a diagnosis of dementia.

Key Messages

Purposeful and satisfying activities should happen as a normal course of the day on one’s own or in small groups. The community should offer opportunities for new learning, religious practices, meditation, art, music, exercise, etc. on a daily basis that meet individuals’ interests and cognitive level. When elders are free to follow their interests and meet their own needs, they feel fulfilled rather than bored.

Personalized materials can be provided and kept in individuals’ rooms, so they are available at all times. Other materials that are sanitized after use, can made available for work on tables throughout different areas of the community. A variety of kits can be assembled with supplies and given to elders who express interest in the topic.

Engagement for individuals living with dementia

Successful activities are often hands-on and involve movement and sensory stimulation they include:

- Arts and crafts

- Writing poetry

- Telling stories, reading books

- Cleaning one’s room

- Washing and folding one’s clothes

- Religious and spiritual practices

- Wood working

- Gardening

- Personalized music listening

- Small group sing-a-longs

- Yoga

- Mindfulness, relaxation and mediation

- Familiar Cards and board games

- Memory books

- Montessori activities (practical life, sensorial, language, mathematics, and culture)

In the absence of a cure for dementia, socialization and engagement in purposeful activities is a powerful treatment for the symptoms associated with dementia. People with dementia still have a need to feel wanted, to learn new information, have relationships with friends and family, and to contribute to the community. Social isolation as a result of COVID-19 puts elders at risk for decline in mental and physical functioning, loneliness, and depression. We would be pleased to provide guidance and additional information for organizations wanting to initiate or expand any specific programs or activities.